Mobilità/Immobilità

“Movement makes connections and connections make inequalities” (Urry, 2012, p. 24)

Guardare alle pratiche di mobilità oggi è un esercizio efficace per leggere e interpretare i processi di trasformazione della città contemporanea.

La mobilità racconta come i luoghi sono costruiti e vissuti. Descrive cioè i modi e i tempi con cui i luoghi sono costruiti attraverso le pratiche e permette di leggere la città a partire dai ritmi che la caratterizzano, così da tenere insieme dimensione spaziale e temporale delle dinamiche urbane, passando attraverso diverse scale dei fenomeni osservati.

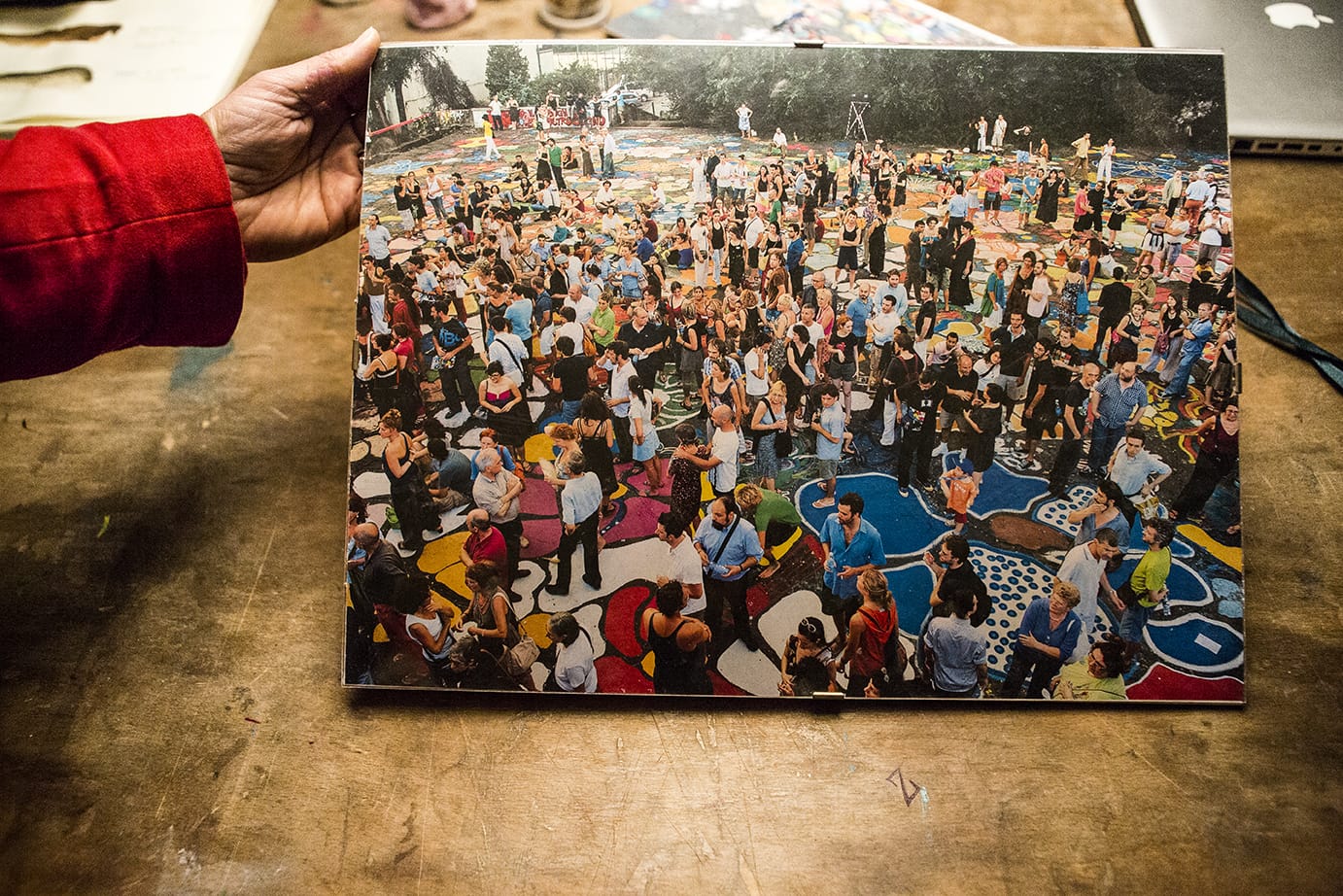

La mobilità racconta le trasformazioni nelle pratiche di lavoro, nella vita familiare, nel sistema di preferenze e nelle abitudini che si riflettono nei modi con cui ciascuno costruisce i propri programmi giornalieri di mobilità e/o di immobilità, poiché la mobilità è un mezzo per accedere alle opportunità urbane e partecipare alla loro produzione.

In questo senso, la mobilità svolge un ruolo fondamentale anche nel determinare le opportunità a disposizione di ciascuna persona, diventando così una condizione chiave per garantire cittadinanza e inclusione sociale; la mobilità rappresenta una risorsa e un valore (Litman, 2013). A partire dalle proprie competenze e risorse, nonché dalle caratteristiche dei contesti urbani di riferimento, essa diventa un capitale utilizzabile per il perseguimento di aspirazioni individuali e collettive (Kaufmann, 2002; Urry, 2012). E’ quindi un (pre)requisito per l’inclusione sociale e, al contempo, produce anche nuove forme di disuguaglianza (Kaufmann, 2002, Le Breton, 2005, Creswell, 2006, Cass et al., 2005) legate alle risorse, alle competenze individuali, alle conoscenze acquisite e alle capacità organizzative disponibili (Tarrius 2000; Orfeuil 2004).

Non si identifica quindi con la sola dimensione spaziale del movimento, ma comprende le reti a sostegno della mobilità, le capacità necessarie per muoversi (Canzler, Kaufmann & Kesselring, 2008); assume molteplici caratteristiche, forme e significati che rendono necessario parlare di mobilità al plurale (Urry, 2007; Sheller & Urry, 2006).

E’ quanto accade anche a Milano, in cui la mobilità cresce più del reddito medio pro-capite e restituisce l’utilizzo più o meno intenso, intermittente e multidirezionale di luoghi, servizi, reti. I dati a nostra disposizione ci dicono che la catena degli spostamenti giornalieri si fa più complessa e articolata nello spazio e nel tempo, con una propensione alla mobilità che cambia in relazione alla condizione professionale e al lavoro ed è accompagnata da un sostanziale ridimensionamento del peso degli spostamenti pendolari, a favore non solo di spostamenti legati allo svago, tempo libero, agli acquisti…. – i cosiddetti spostamenti “a sistematici” – ma anche dall’emergere di nuove forme di mobilità.

Queste mobilità emergenti restituiscono gradi diversi di adattamento all’incertezza crescente del mercato del lavoro e dell’imperativo sempre più forte verso la flessibilità.

Esito dell’effetto congiunto del mercato del lavoro che richiede una flessibilità via via maggiore ed è sottoposto a gradi di incertezza crescenti, di una riconfigurazione spaziale e temporale delle attività lavorative che oscillano tra tendenze di ri-concentrazione e nuovi processi di periferizzazione, ma anche dell’offerta di reti di trasporto e di comunicazione che consentono l’allungamento degli spostamenti giornalieri, queste nuove forme di mobilità esprimono domande di servizi specifici a cui non sempre ciò che è disponibile dà risposta.

Dal pendolarismo giornaliero di lunga distanza (oltre i 150 km al giorno) che, in molti casi, costituisce una alternativa alla rilocalizzazione residenziale e, spesso, è determinato da vincoli legati al mercato del lavoro, alle condizioni familiari e che ha in Milano un recapito importante, alla multiresidenzialità che riguarda lavoratori che vivono in città da lunedì a venerdì, ai lavori della notte caratterizzati da slots temporali a-tipici e che non trovano nell’offerta di mezzi pubblici soluzioni alle loro domande di mobilità, ai cosiddetti “frequent walkers” persone che coprono regolarmente una distanza di circa 5 km in un’ora al giorno a piedi, alcuni per scelta, altri per esigenze o vincoli diversi quali l’assenza o la non disponibilità di risorse per altri mezzi di trasporto (Pucci, 2018).

Non leggiamo tuttavia le forme diverse che può assumere la immobilità: se cioè la immobilità è una scelta, oppure un vincolo che genera disuguaglianze nell’accesso alle opportunità.

Di questa condizione poco ci viene restituito dai dati sulla mobilità disponibili.

Per riconoscerla non possiamo basarci su domande di mobilità esistenti, che spesso riguardano persone già con una buona mobilità, con il rischio cioè di proiettare nel futuro le stesse disuguaglianze di accesso ai beni e servizi urbani.

Possiamo invece spostare la nostra attenzione sull’accessibilità reinterpretandola come “indicatore sociale” della capacità di ogni individuo di partecipare alla vita sociale, quindi come condizione per garantire a ogni individuo la partecipazione alle attività di un territorio (Geurs & van Wee, 2004).

In questo contesto, alcuni autori (Martens, 2017; Lucas, 2012) hanno offerto una nuova prospettiva, ponendo attenzione verso le persone e il modo in cui i sistemi di trasporto contribuiscono alla loro accessibilità, assumendo che l’accessibilità di una persona dipenda sia dalle condizioni di contesto (sistemi di trasporto e modelli di utilizzo del territorio), sia da caratteristiche individuali (competenze, capacità personali, preferenze, ma anche reddito, proprietà del veicolo…).

Concetti quali “activity participation” o “basic accessibility” (Martens, 2017), proposti in questi approcci, offrono una prospettiva operativa per affrontare le diverse forme di disuguaglianza nel partecipare alla vita sociale di cui alcune forme di mobilità e alcune forme di immobilità danno conto.

Privilegiando cioè una visione strumentale della mobilità, considerata come mezzo per accedere alle opportunità e partecipare alle attività quindi come “capitale spaziale”, diventa possibile indirizzare gli interventi verso il miglioramento selettivo dell’accessibilità, privilegiando soprattutto le persone che sperimentano direttamente limitate opportunità di mobilità o immobilità forzata, a causa delle condizioni attuali di offerta di servizi per la mobilità.

In questo modo, l’equità è garantita non tanto da un’equa e isotropa distribuzione dell’accessibilità, ma piuttosto da azioni selettive che affrontano i problemi più urgenti di accesso alle opportunità di base di una comunità.

Paola Pucci

On fairness in the domain of transport

The upper and lower limit of government intervention

THE NEED FOR A REAL TRANSITION

Over the past decades, many have called for fundamental changes in transport policy. The proponents for change have typically pointed at the enormous negative impacts of a car-based transport system. My claim is such ‘green’ arguments will not bring about real change, but that real transition in the domain of transport can only come about if we recognize that mobility is a prerequisite for full participation in society – and if we understand that governments have to guarantee, as much as reasonably possible, that all can participate in society.

The recognition that mobility is a prerequisite for full participation in society means that a lack of mobility can put people at risk of social exclusion. Research from around the world shows that this risk is real: studies from the UK have shown that poor transport is a barrier for two out of five job seekers to obtain a job; a study in Flanders shows that nearly seven in ten low income jobseekers have problems to get a job because of lack of mobility.

The notion of transport poverty can be formalized by recognizing that there is a relationship between a person’s level of mobility, accessibility, and activity participation. Given a fixed land use pattern, a higher level of mobility, for example because of access to a faster mode of transport, will automatically lead to a higher level of accessibility. A higher level of accessibility, in turn, is conducive to a higher level of activity participation.

The relationship between accessibility and activity participation is obviously not linear in character. It may be expected that a drop in accessibility will result in a decrease in the level of activity participation. This reduction is not problematic, as long as it does not have real effects on the quality of life. However, as accessibility further decreases, full participation in society may be hampered. When this occurs, people experience transport poverty. A level of accessibility below this lower limit is unacceptable, given the broadly shared understanding that government intervention should guarantee everybody a decent minimum – also in terms of their ability to participate in activities out of the home.

This analysis implies that the first responsibility of government lies in ensuring a minimum level of accessibility. Deviations from this principle may be acceptable, especially if the size of the group with a low level of accessibility is small and the cost of improving their accessibility, which are to be borne by the whole community, are disproportionately high. It is less obvious to derive an upper limit from the claim that mobility is a prerequisite for full participation in society. The relationship between mobility, accessibility and activity participation does not directly delineate an upper limit. Yet it is clear that the marginal benefits of additional accessibility, as generated by improved mobility, decrease as the initial level of mobility and accessibility go up. In other words, improvements in accessibility will have smaller and smaller impact on the level of activity participation as accessibility goes up. At a high level of accessibility, further improvements are more likely to induce persons to make different choices, in terms of destination or types of activity, than to actually contribute to a further increase in activity participation. When this occurs, additional investments in accessibility are no longer required in order to guarantee full participation in society. This, then, is the upper limit: government intervention is no longer needed if it does not increase activity participation.

This does not imply that additional investments in accessibility above the upper limit are out of the question. If citizens attach great importance to accessibility beyond the reasonable upper limit, they must be allowed to realize that without additional public funds. In other words, investments in infrastructure should be self-financing. The upper limit also allows for additional public investment where it would be desirable for other reasons than activity participation, such as improving the economy or environmental protection. Such investments, however, are not part of transport policy, but rather of economic or environmental policies which use transport investments as a means to achieve a particular, non-transport, goal. Transport policy should focus on the goal to enable activity participation by securing the lower limit and avoiding ‘excessive’ public investments when the upper limit has been achieved.

MAKE NO SMALL GESTURES

Translated to practice, the above implies that transport policy should no longer guided by the intensity of traffic congestion. The fact that everyday motorists join the traffic jam actually underlines that the transport system is of sufficient quality to enable activity participation. The real transport problem must be sought in the existence of latent demand for travel. Real transport problems occur when people want to make trips, but do not do so because of the poor quality of the transport system. These are the cases in which interventions in the transport system are necessary. For instance, a recent study conducted in Rotterdam shows that low-skilled job seekers cannot obtain work in part because of a lack of public transport services to industrial estates located along highways. It are precisely these ‘missing links’ in the network that are in need of ‘repair’. If we do that in a smart way, with high quality public transport services, we may also induce people to switch from cars to public transport, thereby reducing traffic congestion. But these are just side benefits. The core aim of such a transport policy is to ensure the conditions for activity participation by everyone.

A transport policy that is based on principles of justice thus goes beyond small gestures to the low-mobile population groups, such as volunteer bus services or wheels-to-work programs. Rather, it requires radical changes in priorities, with the bulk of public funds to be used to guarantee the lower limit. For most countries, it will entail a substantial shift from investment in asphalt and high speed rail, to investments in high quality regional and urban public transport. Since one bus an hour for everybody does not provide the kind of accessibility that enables persons to really participate in activities, priorities will have to be set. These should go to areas with large numbers of people who are dependent on public transport and where maximum benefits can be generated in terms of an increase in activity participation. This means that high frequency connections to and from poor urban areas are preferred over an occasional bus to every village in the rural areas. Fairness also requires an efficient use of resources.

The application of the lower and upper limits in transport policy will actually imply an end to the much-criticized predict-and-provide approach in transport. This would be a radical break with the past, but at the same time it would lead to a normalization of transport policy. Few areas of government intervention consider it their responsibility to meet unrestrained demand. For instance, setting limits is an inevitable task in the domains of health and education. Like in the field of mobility, both domains are confronted with a seemingly infinite demand for services. There is virtually no limit on the demands for better education and for better health care services. However, in neither area ‘demand’ is considered to be the sole guide of government intervention. Indeed, the term ‘demand’ as employed by economists, plays only a minor role in both domains. Rather than demand, the upper and lower limits of government intervention in both health and education are determined by budget constraints. The egalitarian nature of both domains implies that the upper and lower limits are very close to each other. A greater bandwidth between the upper and lower limit is inevitable in the domain of transport, not in the least because differences in accessibility between center and periphery are inevitable. But this observation does not mean that the demand for transport should be leading in government policies. Rather, it seems in line with broader government practice in health and education, to set limits on the responsibility of government to serve the ever-increasing demand for travel.

My claim is thus that justice should be at the heart of any transport policy and that the notion of justice can be the starting point for a true transition in the domain of transport. Such a transition would build on the understanding that mobility and accessibility are conditions for full participation in society. Accepting this premise as a basis for policy would lead to a radical change in government responsibility in the domain of transport and to a radical shift in policy priorities. It would bring transport policy in line with the widely accepted doctrine underlying government intervention in the areas of health and education. It is this similarity that makes me belief that a transition based on principles of justice is much more likely to succeed in the long term, than a transition based on concerns about the environment alone.

Karel Martens