Come si è costruita l’identità collettiva che ha consentito a Donald Trump di diventare il Presidente degli Stati Uniti? Chi sono i suoi elettori?

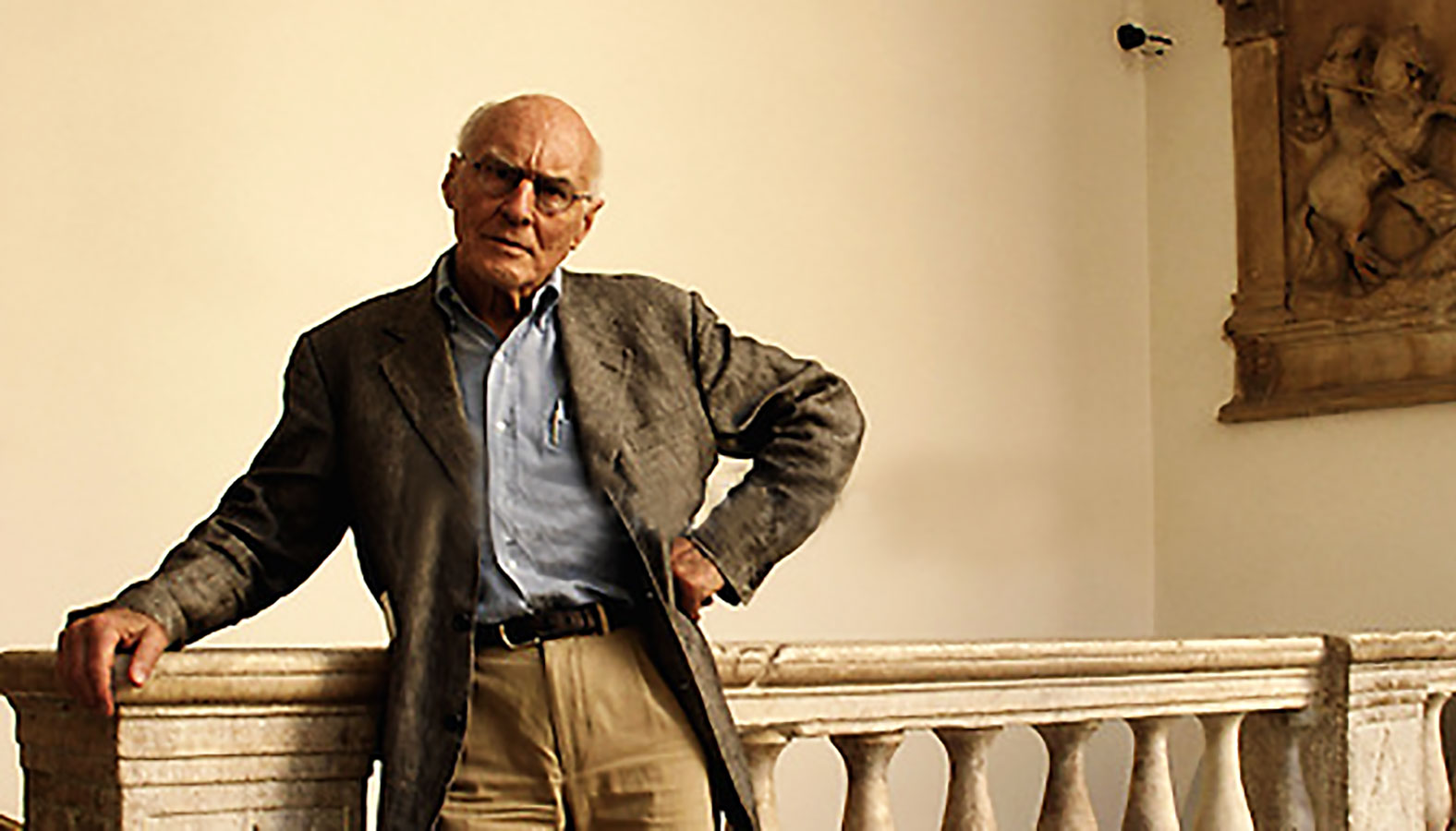

Sidney Tarrow, professore emerito di Scienze Politiche che ha studiato i fenomeni dei movimenti sociali e docente alla Cornell University, cerca di trovare una risposta a queste domande sfruttando l’eredità culturale del sociologo Alessandro Pizzorno, cui Fondazione Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, in collaborazione con il Dipartimento di Scienze sociali e politiche dell’Università degli Studi di Milano, dedica la prima edizione del Convegno internazionale ‘L’azione collettiva fra identità e rappresentanza – Movimenti, organizzazioni degli interessi, partiti’.

Una riflessione che mette a fuoco la categoria di “identità collettiva” a cui lo studioso triestino ha dedicato alcuni dei suoi studi più importanti e che sono diventati un punto di riferimento imprescindibile per la sociologia.

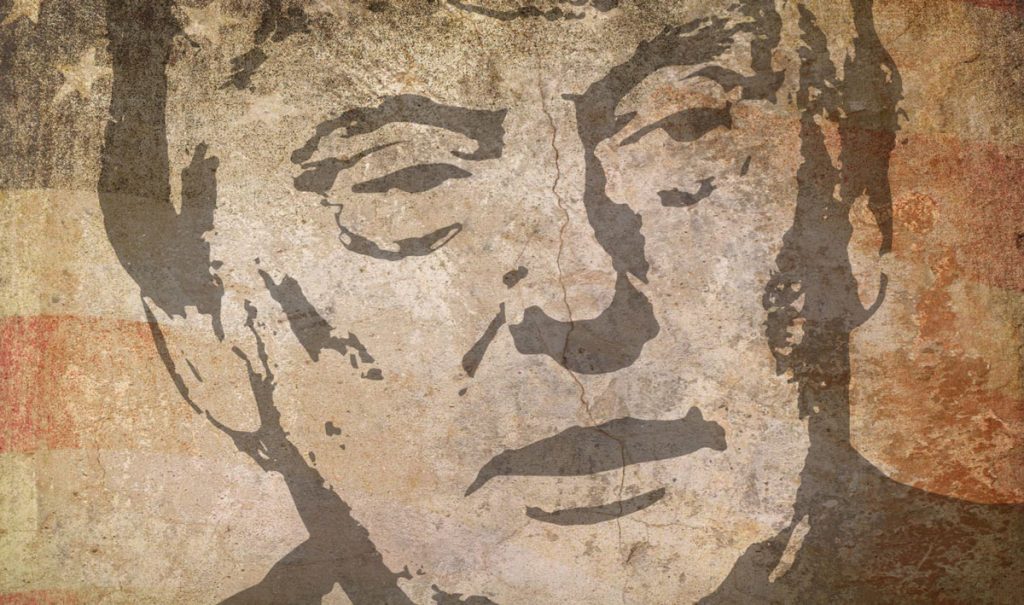

In un’epoca di sempre più forti polarizzazioni sociali, etniche e religiose, Donald Trump è diventato il leader del Partito Repubblicano, unificando il suo elettorato sotto lo slogan “Make America Great Again” fino all’elezione del 2016, in quella che è stata definita “la manifestazione di una più ampia crisi identitaria del Paese”, a dimostrazione della lezione pizzorniana per cui una nuova identità collettiva emerge dopo un periodo di intensa conflittualità socio-politica. In questo percorso quali sono gli elementi di contiguità rispetto all’avanzata populista che sta contrassegnando la disgregazione della comunità europea? Quali invece le differenze che caratterizzano la specificità del “trumpismo”?

Proponiamo qui un’anticipazione della relazione che Sidney Tarrow terrà domani in occasione della prima edizione del Convegno internazionale ‘L’azione collettiva fra identità e rappresentanza – Movimenti, organizzazioni degli interessi, partiti’.

Documento tratto dal patrimonio di Fondazione Giangiacomo Feltrinelli

Putting Sandro Pizzorno and Donald Trump in the same presentation – let alone in the same sentence! – may raise a few eyebrows, although I suspect it would have produced a wry smile on Sandro’s face. But in his work on political exchange and collective identity in The resurgence of class conflict in Western Europe with Colin Crouch (1978: vol II), and in his later writings on “identity and recognition”, Sandro provided a theoretical roadmap that can help us to understand a variety of phenomena of right and left – including even the strange phenomenon of Trumpism in the United States – a constructor of identity if there ever was one.

Sandro was interested in how new social subjects are formed in the crucible of periods of intense conflict and cultural confusion. His approach had three main foci: first, interest and identity are melded together (1983); second, in periods of intense social conflict, collective identities are dynamic rather than static; and, third, the develop in tension with mainstream groups and established institutions. In the case he studied in the 1960s, Sandro saw new groups of workers struggling to construct new collective identities in interaction with the main trade union institutions and in conflict with the capitalist system.

Sandro begins his discussion of the new workers’ collective identity, not with a typology or with a definition, as in the cases of the authors I have just mentioned, but with a discussion of the structural conditions of its appearance in the late 1960s. New collective identities arise, he writes, in “periods of destabilisation and conflict” (p. 292), when there is a “growing autonomy of sub-units” (p.293), when “the logic of exchange and negotiation is unknown or abolished…expressive conduct will replace instrumental conduct…direct participation will be felt to be necesary since representation is excluded and trust is not yet grounded”. Most important in his account, “recognition and identity (or, more precisely recognition of a common identity both on the part of others and among the participants themselves) will be the goal of the action” (p. 293).

Extending the Scope Conditions of Pizzorno’s Theory

The dynamics that Sandro described in his 1978 chapter were not intended to be limited to industrial conflict: “Slightly different in its origins and its consequences is the case of the formation of collective identities for groups of people who do not have a separate identity in the organization of production: for example, youth, students, women, ethnic or religous minorities etc” (pp. 293-4).

Trumpism as an Identity Movement

Despite its long history as a democracy and the supposed dominance of the “medium voter’ in its politics, the United States has been periodically subject to waves of identity politics. But as Sandro would have agreed, each period of conflict grew out of conflicts of interest with a number of different axes that congealed into a single polarized conflict. Never was this more true than in the sectional conflict that eventually exploded into the civil war of 1861-65 (Tarrow 2015:ch. 2). I will argue that the United States is going through a parallel – though less violent – period in which a number of different axes of conflict are congealing into a single collective identity.

The election of Donald Trump has given rise to a great deal of “identity talk.” As two Turkish observers, Esen and Yarmimci-Gevickci, summarize; “Scholars generally attribute Trump’s election to his success in adopting an identity-focused framing on wedge issues (e.g. immigration) at a time of rising ethnic and racial polarization.” Similarly, Sides, Tesler, and Vabreck (2017:35) described the 2016 election as “the manifestation of the country’s broader identity crisis”.[1]

But Trump’s “base” did not come from a single pre-existing racial/ethnic group; his campaign – which actually began in 2012, with his insinuation that Barack Obama was not an American, played into the fears and resentments of a number of partially-connect social and political groups: white, non-college-graduate voters who werre distressed by the rise of mlticulturalism….”; authoritarian voters with his portraual of various groups including immigrants and Muslims as threats to the United States” (Ibid); and opponents of gender equality, concretized in his appeal to white, middle-aged voters. “Republicans are more likely to be whiter, older, wealthier and more likely to be male and Christian than the American public. This is embracing identity politics,” wrote one observer.[2]

Donald Trump – despite his far weaker understanding of American politics than that of “the great communicator” – outstripped Reagan in his ability to unify the different strands of American conservatives behind a message of national unity – “Make America Great Again” – an empty signifier that meant something to each of them. Trump created a powerful coalition based on racial resentment, economic nationalism, neo-liberalism, and nostalgia for a past in which white, male Protestants dominated the country.

Back to Pizzorno

Between the new collective identity of the insurgent elements of the European working class that rose up in the late 1960s and the Trumpian movement that has apparently successfully taken over the American Republican party, there are very few parallels. But one parallel stands out amid the differences: the emergence of a new collective identity out of a period of intense political and social conflict. In the case of the insurgent working class of the late 1960s, this identity emerged in industrial conflicts in the context of a trade union movement that provided the armature for collective action but against which new actors could fashion new identities in the struggle against capitalism; in the case of the Trumpian movement in the United States today, the Republican party provides the armature for the new movement to attack what Trump and his enablers have begun to call “the deep state.”

There are great dangers for democracy in the rise of the Trumpian movement and in the apparent surrender of an important part of the Republican party to its leader (Levitsky and Ziblatt 2018). I do not want to minimize the danger of an authoritarian inversion resulting from the current “Trumpian moment;” but it is also worth remembering another lesson we can glean from Pizzorno’s intellectual heritage: that cycles of contention pass through institutional mechanisms, which intervene in their shape and their conclusion. And as Sandro wrote in his 1978 essay;

…it is high time that attention be paid to periodic variations in certain phenomena. Otherwise, at every new upstart of a wave of conflict we shall be induced to think that we are at the verge of a revolution; and when the downswing appears, we shall predict the end of class conflict (1978: 293).

[1] Berk Esen and Sebnem Yarmimci-Gevickci, An Alternative Account of the Populist Backlash in the United States: A Perspective from Turkey. PS: Political Science and Politics 52 (July 2019).

[2] Eugene Scott, “Republicans despise identity politics. Trump wants to immerse his campaign in it,” Washington Post, June 22, 2019.